“LAS CARAS LINDAS DE MI GENTE NEGRA”

January 21, 2020

by Danielle Brown, Ph.D.

Black Musicians in the Spanish Speaking Americas

I once said to a friend after just meeting their Honduran friend, “You know, up until now, all the Hondurans I know have been Black.” In fact, so were all the Panamanians I knew, like my brother’s godmother who always had a cuento for my mom.

Peruvian singer, Eva Ayllón always looked to me a lot like my paternal grandmother. And in high school, when I’d travel to Lawrence, a Dominican enclave in Massachusetts, I was always inevitably asked if I was “Juan’s”—some Dominican man’s—daughter.

Then there was the time I’ll never forget, when my middle school music teacher, the late great Roy A. Prescod, surprised the heck out of some of my Puerto Rican classmates who had been speaking in Spanish (and maybe even talking badly about him). When he opened his mouth and gave them a piece of his mind in Spanish, jaws dropped and mouths hushed.

There was also that time in Mexico, while standing at the back of a Catholic church, a Mexican woman approached me and told me she liked my [natural] hair style. She wanted to know how I created the style so she could teach her sister who has hair like mine.

And even though I’ve never personally met a Black Ecuadoran, I remember watching the World Cup at my family’s home in Trinidad in 2006. Ecuador was playing who knows who, but the entire team on the field was Black. And I remember thinking to myself, “We are everywhere.” “We” meaning Black people.

I grew up in New York City, a place where many identities converge. As a result, I perhaps had more opportunities than others to come into contact with complex identities that are not always represented in our classroom curricula, media, and elsewhere. Black people have existed in the Spanish-speaking Americas for centuries, at least since the 16th century, in large part due to the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade. Yet their presence has only been acknowledged significantly in the mainstream over the past few years, particularly as the term “Afro-Latinx” has gained currency in the media. While the concept may seem new to some, it is not. “Afro-Latinx” has a long history in Black movements of the 19th and 20th centuries, including Pan-Africanism and the literary focused Negrismo and Negritude movements, which sought to unify Black people across the globe through common ancestry in Africa. More recently, Black identity in the Spanish-speaking Americas gained renewed interest in the aftermath of the 2001 United Nations World Conference Against Racism in Durban, South Africa.

Although the term Afro-Latinx has become part of our common lexicon, its use is not without problems. Below, I refrain from using the term Afro-Latinx and choose instead to use the word Black (Sp. negr@) as a way of reminding people that Afro-Latinx and related terms evolved to center and empower African-descended people that historically have been marginalized, and whose identity is not negotiable—that is, their blackness cannot be masked. My decision to not use the term is done with a keen awareness that the word has been used by some afrodescendientes whose self-identification never included a connection to blackness or Africa. Their claim to the identity is done primarily to align themselves with what they perceive to be the “coolness” or social currency of being Black, without having to confront the lived realities of those for whom not only genotype marks them as descendants of Africa, but phenotype as well. As with all terms, the word “Black” is not unproblematic, as its meaning in the Spanish-speaking Americas and elsewhere is not monolithic and is directly connected to the culture and history of a people and place. Nonetheless, Black is the term that I prefer to use.

5 Black Musicians from the Spanish-Speaking Americas

Generating a list of even 5 notable Black musicians from the Spanish-speaking Americas is not an easy task, primarily because there are so many great artists from which to choose. These musicians have performed at the highest levels across genres and styles, playing music deemed traditional, folkloric, and contemporary; they have played music from their homeland and abroad. In addition, their music reflects the cultural and musical exchanges that were the result of historical migrations of Black people throughout the region, from enslaved Africans and creoles brought to Cuba from Haiti around the time of the Haitian Revolution to Black people from the English-speaking Caribbean who settled in Cuba and Central America as they searched for work in the post-emancipation era. In addition, their music reflects the rapid global flow of music that has characterized the 21st century. The work of the musicians named below represents a small fraction of the output of Black musicians from the Spanish-speaking Americas. In an effort to provide some level of breadth of representation, the musicians that I have included come from across the region, from the Caribbean, Central America, and South America. Some of the musicians are well-known, others not so much. Nonetheless, all in some way have worked to better the lives of Black people who have been marginalized in their home country and abroad.

Amelia Pedroso. Retrieved from http://www.afrocubaweb.com/ameliapedroso.htm

Amelia Pedroso: Cuba

Cuba is world-renowned for its many talented musicians, many of African descent. Although Amelia Pedroso Acosta (1946—2000) is perhaps lesser known on the international stage than some of her compatriots, her contributions to Cuban music, and by extension the world, is enormous. Pedroso is best known for her work as a priestess and akpón, or ritual singer, within the orisha-based faith known as Regla de Ocha (or Santería) in Cuba. Pedroso was controversial for disrupting norms which restricted women and homosexuals from certain religious activities. She pioneered the practice of women playing the batá drums traditionally played only by men and created an all-female ensemble called Ibbu Okun. A lesbian, she also created a space for queer practitioners of the religion. She has served as an inspiration for many female akpones, batá players, and queer practitioners for her efforts to offer them a space free from religious constraints based on gender and sexual orientation. May 24, 2020 marks the 20th anniversary of her death and will be marked by a special presentation in New York by Lukumi Arts.

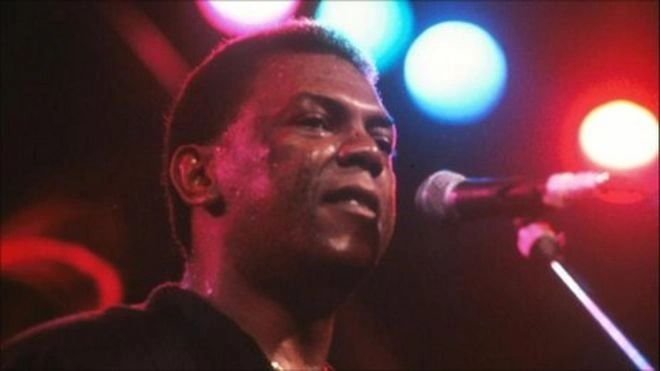

Joe Arroyo. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-14152437

Susana Baca. Retrieved from https://www.songkick.com/artists/61055-susana-baca

Joe Arroyo: Colombia

Álvaro José Arroyo González (1955—2011), more popularly known as Joe Arroyo, was a Colombian musician and songwriter. He was born and raised in Cartagena, Colombia, a city which had once been a major slave port. He first rose to fame as a vocalist with the popular salsa group Fruko y Sus Tesos before forming his own band, La Verdad, and gaining success as a solo artist. One of his best-known tunes, “Rebelión” (“Rebellion”)—also known as “No le pegue a la negra” (“Don’t Hit the Black Woman”)—is not only a favorite of salsa dancers, but also one that reflects Arroyo’s life-long commitment to better representation and treatment of Black Colombians. Other popular tunes include “En Barranquilla me quedo” and “La noche,” the latter of which has been sampled or covered by many artists, including covers by Juanes and Elvis Crespo, and Don Omar’s sampling of the same in his song “Dile.” “Rebelión” was recently sampled in J Balvin’s song titled “La Rebelión.”

Tite Curet Alonso: Puerto Rico

Catalino “Tite” Curet Alonso (1926—2003) was a highly prolific and influential songwriter. He is said to have authored over 2000 songs, many of which were adopted and arranged for some of the most notable artists and groups of his day, many of whom sung under the Fania Label, including Hector Lavoe (“Periódico de ayer”), La Lupe (“La tirana”), and Cheo Feliciano (“Anacaona”). His songs spanned the gamut of human experience from love to politics and he was especially known for writing songs with socially conscious messages, including “La Abolición” and “Pueblo Latino.” Interpreted by Pete “el Conde” Rodríguez, the songs respectively speak to the continued hardships of black people despite the abolition of slavery and the need for the Latin American community to unite and tackle injustice. One of Tite’s most beloved songs, “Las caras lindas (de mi gente negra)”—"The Beautiful Faces (of My Black People)”—is a song of pride and ode to black people and was made famous by Afro-Puerto Rican singer Ismael Rivera.

Aurelio Martinez. Retrieved from https://www.northcountrynow.com/hometown-photos/norwood/aurelio-martinez-perform-norwood-today

Aurelio Martinez: Honduras

Aurelio Martinez (1969—Present) is a Garifuna musician and politician from Honduras. The Garinagu are descendants of Africans and indigenous people from the island of St. Vincent who were forced into exile by the British, settling eventually in the Central American countries of Belize, Honduras, Guatemala, and Nicaragua. Martinez is considered one of the foremost tradition-bearers and ambassadors of Garifuna music and culture. In 2006, he became a congressman in his native Honduras. He was the first Garifuna in the region to hold such a position, which he used to fight for Garifuna rights and interests. He is part of a tradition of musicians maintaining and sharing Garifuna traditions with the world. He has received acclaim for his solo albums Garifuna Soul and Lándini, his work on the Paranda: Africa in Central America album, with tracks from several esteemed Garifuna musicians such as Andy Palacio and Jursino Cayetano, and his participation on the WATINA album with Palacio and The Garifuna Collective.

About the Contributor

Danielle Brown, Ph.D. is an artist, scholar, and entrepreneur. Brown earned a doctorate in Music from New York University with a concentration in ethnomusicology and specialization in the music of Latin America and the Caribbean. She is the Founder and CEO of My People Tell Stories, LLC and directs the Caribbean Music Pedagogy Workshop, a summer professional development workshop for teachers. She is the author of the music-centered ethnographic memoir, East of Flatbush, North of Love: An Ethnography of Home, and the East of Flatbush, North of Love: Teacher Guidebook. Brown is a 2018 NYSCA/NYFA Fellow in Folk/Traditional Arts and is a Visiting Scholar in the Department of Musicology at the University of Miami for the 2019—2020 school year. More information about Dr. Brown and My People Tell Stories can be found at www.mypeopletellstories.com.